Luck is the residue of hard work, Gary Player is prone to saying, an admonition he is quick to credit his father, who worked as a captain in a gold mine 12,000 feet underground, and taught him by example that with hard work he could do anything.

“I was with him one time when he finished work,” Player said. “He took off his shoes and poured water out. I asked him why he was walking around in water. He said he wasn’t. That was his sweat.”

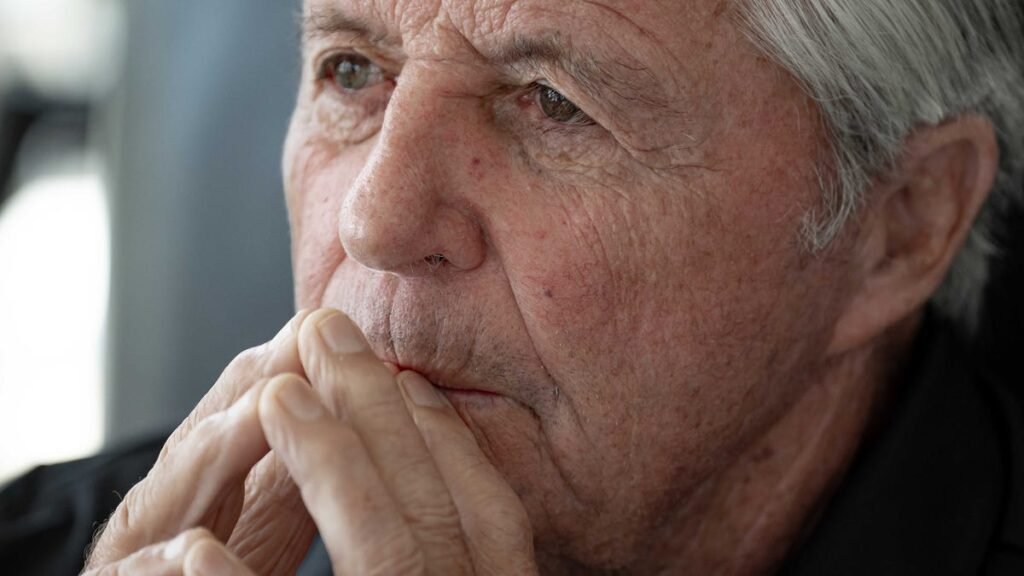

Player became a man to whom sweat was the perfume of life. Player, who turns 90 today, set the standard for worldwide tournament play, having won more than 100 titles, including nine major championships on both the PGA Tour and PGA Tour Champions. Above all else, his father’s words rattled in his head and imbued in him this core philosophy that would guide him throughout his life.

Born Nov. 1, 1935, Player was the youngest of three children to Harry and Muriel Player, who died from cancer at age 44, when Gary was 8. As a youth, he left the house each morning at 6 a.m., boarded a streetcar, and then hopped on the No. 68 bus to attend the finest school. Looking back on his adolescence from the perspective of his own adulthood, Player said, “If it’s possible, school took the place of my mother. It made me tough, and it made me hungry.”

Hungry enough that Player, who turned professional at age 18, slept on the beach in his waterproofs his first night in St. Andrews in 1955. “The price was right. The room service was lousy,” he joked. “Now I go to the Open Championship and I watch all the pros arrive in these big jets. I used to go by Greyhound bus.”

On the basis of a letter of recommendation from his father, Clifford Roberts, chairman of the Masters Tournament, invited Player to compete in the 1957 Masters. Already a confirmed internationalist, Player made his first trip to the United States, and won his first of three green jackets in 1961. Traveling the world became his university.

“I’ve been on the road for 72 years,” Player said. “Think about that! I’ve traveled more miles than anyone.”

It’s funny that longevity became one of Player’s calling cards. He chuckles at the memory of a long-ago conversation with Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer in which he and Nicklaus insisted they would be hanging the spikes up at the ripe old age of 35.

“We were quite serious about that,” Player said. “Arnold, of course, planned to play forever.”

A few years later, after his 35th birthday, Player walked into the Champion’s dinner at the Masters and Palmer kidded, “What are you doing here in this field? I thought you’d be retired by now.’ ”

Player continues to circle the globe with the drive of the Energizer bunny.

“In the days when I was working very closely with him he’d complain, ‘I can’t do all this. I’m going to die young.’ And it’s true, nobody would’ve done what he did,” IMG’s Alastair Johnston said. “He’d fly from Tokyo to Lima, Peru to Madrid, Spain and then home to South Africa. When I’d tell him what he was going to make he’d say, ‘$50,000! Are you kidding me? I’ll swim there.’ ”

Player was the first to take a holistic approach to golf. He still preaches the benefits of diet and exercise with missionary zeal to anyone who will listen. He dreams of hitting the first tee shot at the Masters when he’s 100.

A decade ago, Player addressed a packed room at the World Golf Hall of Fame when it was located in St. Augustine, Florida, at the unveiling of an exhibit highlighting his career. To hear him speak is to listen to a great performer weave a tapestry of anecdotes with the vividness and detail of a master storyteller. Some say it’s an act, but if it is his adoring audience still leaned forward to soak up his every word.

“I don’t want to be remembered as a golfer who just hit a 7-iron close to the hole,” he explained. “So when I talk about health and wellness, man, that’s my topic. Because my body is a holy temple.”

Just as he obsessively trained to outdrive Nicklaus off the first tee at Augusta. He is just as determined to make a difference in the lives of children. He recites his hero, Winston Churchill, saying, “The youth of the nation are the trustees of posterity.” These are not mere words he’s committed to memory. Through his Player Foundation, he has funded a school from kindergarten through high school much like the one he attended as a kid on the grounds of his ranch, named Blair Atholl. Each holiday season, the youngest students perform a concert. One of the songs they sing is “Gary Player had a farm E-I-E-I-O.” He has one more task to complete as he enters a new decade and closer to becoming a centurion.

All these years later, Player seems no closer to retiring to that farm than the day Palmer called him out for still chasing the little white ball around at 35. Which begs the question: could he ever retire?

“I’m convinced he couldn’t,” Johnston said. “He’s had plenty of opportunities to stay at his farm but he doesn’t. There’s a reason.”

“Rest is rust,” Player said.

Now a nonagenarian, he intends to whistle his way through the graveyard. It is the life he made for himself and the one he chooses to live. Player signed off from his Golfweek phone interview to ready himself for a black-tie dinner in which he is the guest of honor. But he isn’t slowing down by any means. The thought of doing so reminds him of the wisdom of Willie Beta, an uneducated black man who worked at his horse farm for years.

“I once asked him, ‘Willie, how old are you?’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’ I said, ‘When’s your birthday?’ He said, ‘Everyday.’ What a philosophy,” Player marveled. “That’s why I believe that age is just a number. Years wrinkle your skin but a lack of enthusiasm wrinkles your soul.”

He paused for a beat. Two. Then he added this qualifier: “I’ll be disappointed if I don’t live to be 100.”

Read the full article here