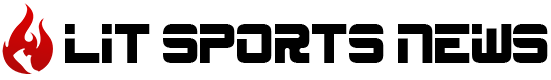

You wouldn’t think it to look at him — this short, fat, bowling ball of a man with the Jersey accent and the cinderblock head — but he was famous once. If you owned a radio and lived in the United States of America during the late 1930s, you almost couldn’t avoid hearing the name Tony Galento.

Sometimes they called him “Two Ton” Tony, on account of the time he showed up late for his own fight and explained that he’d had two tons of ice to deliver in his truck on his way to the arena. Other times he was known as “The New Jersey Nightstick” due to his willingness to use his entire rotund body in a fight, head-butting and eye-gouging and foot-stomping his way to victory. John Kiernan, a sportswriter for The New York Times, once dubbed him “the Falstaff of pugilism,” the implication being that he was fat, funny, flawed and fascinating — but not exactly someone to be taken too seriously.

Advertisement

Other times the nicknames needed no explanation beyond a clear look at the man. Names like “The Orange Orangutan” and “The Walking Beer Barrel” and “The New Jersey Jellyroll” and “The Human Butcher Block.”

He stood all of 5-foot-8 and weighed in around 235 pounds. That doesn’t include the time he missed weigh-ins altogether, having fallen asleep in a movie theater after winning a bet against a man who said Galento couldn’t eat 50 hot dogs in one sitting prior to a fight. He ate 52, then went to the movies to “digest” and was discovered later, slumped in a seat and snoring loudly. For winning the bet, he received $10. Then he won the fight too.

Who’d have thought a man like this, a living cartoon character with a beer in one hand and turkey leg in the other, would ever get a shot at the heavyweight championship of the world? And who could have predicted that, for the briefest of moments, he would stand triumphant over one of the greatest heavyweights of all time, sending shockwaves rippling through radio speakers all over the country?

The fact that he would have to pay in blood for this fleeting glimpse of glory, well, that was just part of the deal. Galento never really learned how to box, is the thing. All he had were those two pot roasts he called fists, a body built for shock absorption, and a stubborn streak that ran through every aspect of his life.

Advertisement

Did America really believe that this combination would be enough to beat the great Joe Louis? Not really, no. But maybe, just maybe…?

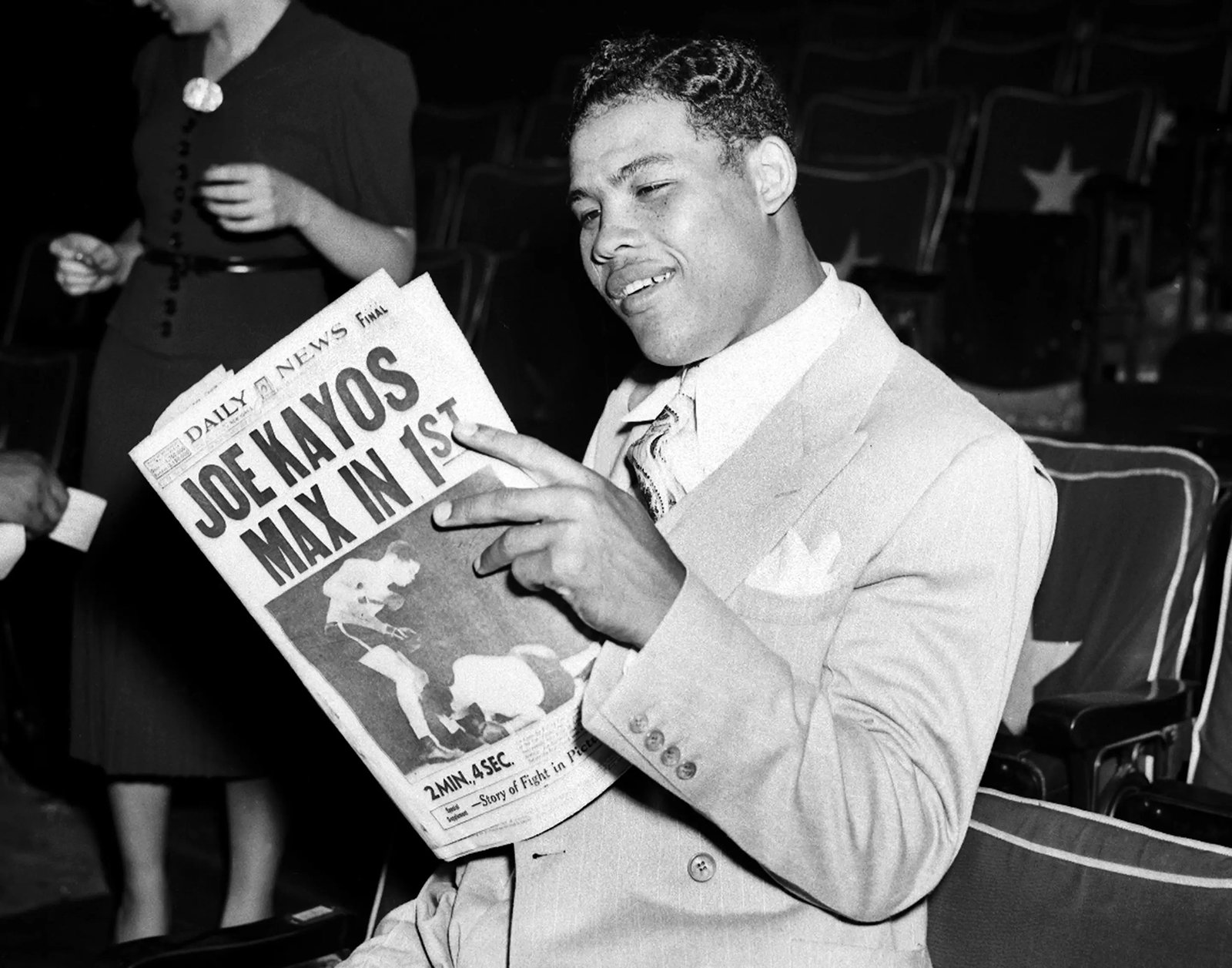

June 3, 1949: “Two Ton” Tony Galento eyes a photo of Joe Louis 10 years after their championship fight.

(Denver Post via Getty Images)

A year earlier, Joe Louis Barrow became a national hero. He was arguably the first Black man to achieve such a status in America. Major League Baseball was still very much segregated, as were the armed forces. Boxing had had exactly one prior Black heavyweight champion — the inimitable Jack Johnson, who had resolved to live his one wild life as if racism simply did not exist — and White America had felt so scarred by the experience that later champs like Jack Dempsey went back to “drawing the color line,” preventing any Black fighter from even getting a chance at the world heavyweight title.

But Louis was different. He was one of the first true boxing stars to rise through a relatively new amateur system in the U.S., winning the Golden Gloves title in his hometown of Detroit in 1933, then winning a national amateur title in 1934. Word spread quickly about the young heavyweight who could box with speed and technical precision while also carrying knockout power in both fists. He made his pro debut midway through 1934 and racked up 12 straight wins before the year was out, earning knockouts in all but two of those fights.

Advertisement

It wasn’t until 1936, at the age of 22, that Louis suffered his first professional loss. It came in the form of a severe beating at the hands of Max Schmeling, a German heavyweight who had briefly been the champion of the world, albeit under some inauspicious circumstances.

In 1930, Schmeling had won the vacant heavyweight title via disqualification following a supposed low blow from opponent Jack Sharkey. For this, Schmeling had his manager — the brilliant but volatile Joe Jacobs — to thank. Jacobs was the one who jumped into the ring crying foul after Schmeling was floored with what some observers insisted was a legal body shot from Sharkey. The referee was apparently swayed by Jacobs’ interpretation, which resulted in Schmeling making history in two ways: He was the first German to win something that could plausibly be called a heavyweight world title, and also the only person to win the heavyweight title via disqualification.

Schmeling bristled at being known as the “low blow champion,” and later lost the title to Sharkey via a controversial decision. (Jacobs, in the immediate aftermath of the judges’ ruling, declared “We wuz robbed,” a phrase that immediately entered the American lexicon and stayed there into the next century.)

Advertisement

But as the Nazi regime took over his home country, Schmeling soon found himself a reluctant symbol. Adolf Hitler pointed to Schmeling as an example of Aryan excellence. When he defeated the previously unbeaten Louis via knockout in Round 12 of their first meeting in 1936, Nazi leaders held it up as proof of their racial superiority. The loss was a bitter pill for Americans who felt themselves tiptoeing toward war with Germany, but that bitterness was magnified in the Black community. After the fight, writer Langston Hughes recalled walking down Seventh Avenue in New York and seeing grown men weeping openly.

“All across the country that night when the news came that Joe was knocked out, people cried,” Hughes wrote in his autobiography.

It was said that Louis had perhaps taken Schmeling too lightly. The German was not known as a knockout artist. He was a smart fighter, careful and technically proficient, but he’d been soundly defeated by the likes of former champ Max Baer, who Louis had demolished in four rounds. For his part, Louis made no excuses. According to John Durant’s “The Heavyweight Champions,” Louis told his mother after the fight: “The man just whupped me.”

June 19, 1936: Joe Louis lies downward on the canvas in the 12th round inside Yankee Stadium after being knocked out Germany’s Max Schmeling.

(New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Louis longed for a rematch with Schmeling, who spent most of the next couple years back home in Germany, fighting infrequently. Louis won the title from James J. Braddock (the subject of the 2005 film “Cinderella Man”) via eighth-round knockout in 1937, but insisted he wouldn’t truly consider himself champ until he beat Schmeling.

Advertisement

On June 22, 1938, he got his chance in Yankee Stadium. American tensions with Nazi Germany had only increased. Germany had effectively annexed Austria just a few months prior, and was now focused on a full takeover of Czechoslovakia. Kristallnacht — the night of the broken glass, a violent pogrom aimed at Jewish homes, business and synagogues across Germany and Austria — would shock the world just a few months later.

Louis’ rematch with Schmeling was now clearly about more than just two men. It was an international conflict, with each man carrying a national identity and ideology on his shoulders whether he liked it or not.

The bout was a bloodbath. Louis, driven as much by his own desire for professional revenge as by any desire to disprove Nazi racial theories, sliced through Schmeling in the first round. Novelist Richard Wright was among the 70,000 spectators at the bout, describing it in his article “High Tide In Harlem” as a geopolitical battle between a “white puppet” and a “black puppet.”

“At the beginning of the fight there was a wild shriek which gradually died as the seconds flew,” Wright wrote. “What was happening was so stunning that even cheering was out of place. The black puppet, contrary to all Nazi racial laws, was punching the white puppet so rapidly that the eye could not follow the blows. It was not really a fight, it was an act of revenge, of dominance, of complete mastery. The black puppet glided from his corner and simply wiped his feet on the white puppet’s face. The black puppet was contemptuous, swift; his victory was complete, unquestionable, decisive; his blows must have jarred the marrow not only in the white puppet’s but Hitler’s own bones.”

Advertisement

The whole thing took just over two minutes. Schmeling didn’t even land a clean punch. In addition to the 70,000 who packed the baseball stadium, it was estimated that more than 100 million people worldwide — and some 70 million just in America alone — listened to broadcasts of the fight on the radio, making it the single biggest sporting event in modern human history at the time. The fight also brought in slightly more than $1 million at the gate (equivalent to around $23 million today), giving boxing its first million-dollar gate since Jack Dempsey was champion.

The celebrations that followed, particularly in Harlem, were massive. Crowds shouted “Heil Louis!” and performed mocking Nazi salutes. It was “the largest and most spontaneous political demonstration ever seen in Harlem,” Wright wrote, “and marked the highest tide of popular political enthusiasm ever witnessed among American Negroes.”

Louis was suddenly a national icon, but his management team, lead by John Roxborough and Julian Black, was acutely aware of how easily White America could turn on their fighter. Roxborough had a profound impact on Louis’ career, as Louis later wrote in his autobiography:

“He told me about the fate of most black fighters, ones with white managers, who wound up burned-out and broke before they reached their prime. The white managers were not interested in the men they were handling but in the money they could make from them. They didn’t take the proper time to see that their fighters had a proper training, that they lived comfortably, or ate well, or had some pocket change. Mr. Roxborough was talking about Black Power before it became popular.”

But Roxborough also knew the expectations for a Black champion in America were very different than they were for White fighters. They established a series of rules for Louis to follow, which included never having his picture taken with White women, lest it lead to the spread of romantic rumors. (Louis later admitted to many affairs with White women, even with famous movie stars, but insisted that both parties knew it was in their best interests to keep such dalliances entirely private.)

Advertisement

In his excellent history, “Two Ton: One Fight, One Night,” Joseph Monninger writes that Roxborough and Black “comprised an all-black management team that was perhaps an even greater marvel than the fighter himself. They had successfully guided Louis to a championship, had brought him to where only one other black man, Jack Johnson, had ever gone. They massaged his reputation in America with infinite care. One of the seven rules established by Julian Black and John Roxborough when they took over Louis’ contract was never to be seen gloating over the sunken body of a white man. Jack Johnson had ignored such social injunctions, and had paid a heavy price as a result.”

The strategy worked, but the shine on Louis also began to wear off somewhat once the Schmeling rivalry had been put to bed. He soon faced a familiar problem for dominant champions: Once a fighter has beaten all the serious contenders, he’s left with only unserious ones, leading to declining box-office returns.

Louis had vowed to stay busy as champion, believing that inactivity from the heavyweight champ hurt public interest in the entire sport. He kept that promise, even when there was no one to fight. This would later lead to claims that he beat an assortment of nobodies dubbed the “Bum of the Month Club,” as in 1941 when he defended his title seven times in one calendar year.

But if a champion can’t find a true and worthy challenger, sometimes the next best thing is a novelty, an oddity, an attraction. And while “Two Ton” Tony might not have been much of a boxer, or even much of an athlete, he was certainly odd. Whatever else he may have been accused of, no one ever mistook Galento for boring or even normal. All he needed was the right promotional push — and he had just the man to provide it.

June 23, 1938: Joe Louis admires his handiwork the day after his rematch with Max Schmeling.

(New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Joe Jacobs — often referred to as “Yussel,” or “Yussel the Muscle” — was a born promoter. He loved boxing from an early age, and had an almost supernatural understanding of how to craft a public narrative in order to sell a fight.

Advertisement

As Time Magazine described him shortly after his sudden death in 1940: “He was not only the most colorful but the smartest manager in the prizefight business. Son of an immigrant Jewish tailor who settled in Manhattan’s hurly-burly Hell’s Kitchen, puny little Yussel Jacobs had to live by his wits to defend himself against his tough Irish neighbors. By the time he was 16, he commanded so much respect that he managed two neighborhood pugs.”

In the “Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink,” David Margolick depicts him as a hard-living, hard-partying night owl who typically got up when the sun went down and spent all night moving and shaking before reluctantly turning in the next morning.

“His father wanted him to be a rabbi,” Margolick writes, “but young Joe gravitated toward boxing; while still in high school he had fighters on his payroll. In military service during World War I, he arranged bouts between rival companies, then promoted fights between soldiers to the general public.”

Jacobs would go on to handle five world champions, but the most notable was Schmeling, who Jacobs essentially poached from a German manager. It was Jacobs who made Schmeling into a household name, branding him with the exotic nickname “The Black Uhlan of the Rhine,” and insisting that publicity was the key to making money in the fight game.

Advertisement

“Not a single day can go by without your name being in the papers,” he is said to have told Schmeling. Jacobs was so valuable to Schmeling that, when Nazi officials told him it was forbidden for Germany’s top sports star to have a Jewish manager, Schmeling appealed directly to Hitler for permission to keep Jacobs in charge of his career.

But even Jacobs had his hands full managing Galento, who went through at least nine different managers — including the former champ Dempsey — during his fighting career.

“I was rotten when I was 12 and I was drinking when I was 15,” he later told a reporter.

Galento had grown up as the son of Italian immigrants in a mostly Irish neighborhood in Orange, New Jersey. He left school early and worked as an iceman, delivering ice first with a horse and wagon and later with a truck. (When his horse died in the street one day, he was inconsolable, weeping openly over the body of his friend and coworker.) He’d been fighting since he was a child, claiming he would settle beefs for other kids in exchange for food. But early on his prizefighting career was little more than a side hustle that he never seemed to take all that seriously.

Advertisement

He drank throughout his training camps. He ate whatever he pleased. Attempts to corral him into something resembling a regular training regime proved fruitless. During Dempsey’s short stint as Galento’s manager, he brought in famed trainer Ray Arcel to whip Galento into shape. Arcel reported back that the whole project was a “waste of time and money.” Galento was, in his words, “just bone lazy.”

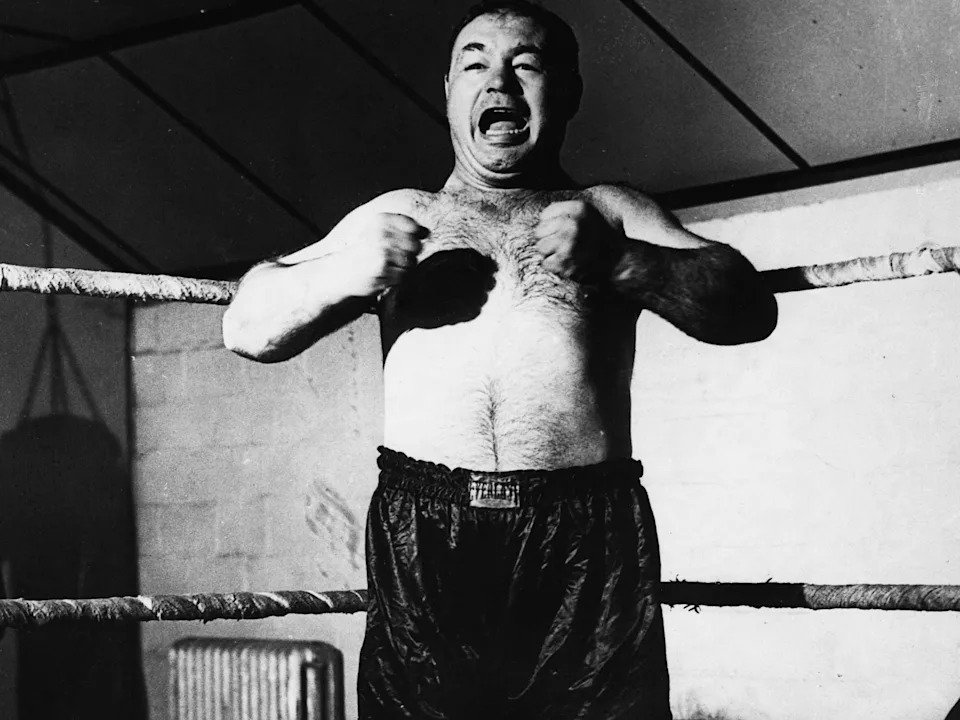

Tony Galento and his famous pre-fight war-cry during his heyday.

(Hulton Deutsch via Getty Images)

He was also uncommonly tough, even in a world of professional tough guys. He had, as one writer put it, “a hippo waist but lion heart.” Galento often took a beating for several one-sided rounds before landing one big punch to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. He fought without a mouthpiece for much of his career, and once took an uppercut that made him bite through his tongue. A doctor administered 25 stitches to repair the tongue, then instructed Galento to stay in the hospital and rest. An hour later, Galento was gone. They found him at a nearby bar, a cold beer in front of him.

Jacobs saw the potential in Galento as the kind of oddball curiosity the boxing world craved. Instead of downplaying his drinking and lack of training, Jacobs leaned into the wild stories about Galento. He told reporters that Galento had once fought off five men who tried to rob him. He told them how Galento would sit down to a dinner that consisted of three whole chickens and a dozen beers. He encouraged Galento to play into his image as an ignorant brute, more ape than man, all id and appetite. When Louis’ name came up, Galento leaned hard into his Jersey accent, saying: “I’ll moida da bum.”

Advertisement

Even famed actor Jackie Gleason later recalled a run-in with Galento, who he claimed heckled him throughout a nightclub appearance and then knocked him cold after Gleason, who didn’t recognize the boxer, asked him to step outside.

“I never saw anybody get up as fast as this guy did,” Gleason said. “Now we get out on Clinton Avenue. I said, ‘Now you’re going to…’ and that’s the last I remember.”

To sportswriters, Jacobs and Galento were a dream pairing. Both made for good copy, tossing out endless quotable quips and anecdotes that were simply too much fun to bother with fact-checking. Dan Parker, of the New York Mirror, once wrote of Jacobs: “If all the newspaper copy he inspired were stretched end to end, a blow would be dealt to the King’s English from which it would never recover.”

Advertisement

When Galento fought Abe Feldman in Miami on George Washington’s birthday in early 1939, Jacobs described it as a bout benefitting “a worthy private charity composed of Mr. Galento, Mrs. Galento, the infant Galento, and myself, though not in the order named.”

Galento described the significance of the bout’s timing thusly: “It is high time the South come to know and love Washington, as we know and love him north of the equator. Why can’t we forget the Civil War and its petty grudges? Washington may have freed the slaves, but remember, he also invented the lightning rod. Let the North and South clasp the hand of friendship on Old Hickory’s birthday — and try to get there early.”

Sportswriters laughed as they wrote, never knowing for sure when he was kidding. But just the look of the man begged for inspired descriptions. When leaning forward to land a punch, one writer said, Galento resembled a chair propped up against a door to halt intruders. John Lardner, writing for the New York Herald Tribune, insisted that Galento’s training had put him “into a new kind of shape, unknown to science … somewhere between a sphere and an ellipsis, with overtones of parabola.” He was so oddly shaped, Lardner wrote, that it wasn’t always easy to distinguish between Galento laying down and Galento standing up, “but when he has a cigar in his mouth, you can tell which is north, and the rest is easy.”

The prospect of such a man challenging for the heavyweight title seemed ludicrous to most knowledgeable fans and media. It was even more absurd now that the champ was Louis, a model of masculinity who appeared to be carved from stone.

Advertisement

But Jacobs knew that good copy could go a long way, especially when presented with just the right touch. He laid out a plan for Galento to fight a series of opponents who Louis had already beaten. If Galento could knock them out in fewer rounds than Louis did, even better. Between 1937 and 1939, the latter being the year of the Louis bout, Galento reeled off 11 straight victories — all of them knockouts, and most of them within the first three rounds.

Between Louis’ need for an opponent who could bring renewed attention and Jacobs’ ability to turn Galento’s faults into newspaper fodder, suddenly the fight started to seem shockingly plausible. It was pitched as an antidote to boxing matches that were technically sound to the point of being boring. Jacobs encouraged comparisons to Dempsey’s fight with Luis Firpo, which saw Dempsey knocked through the ropes. This would be a wild brawl that, regardless of whether it was competitive, would be entertaining. He even asked sportswriters to publicly promise that, if and when Galento knocked Louis through the ropes, they would not help Louis reenter the ring, as the press had done for Dempsey.

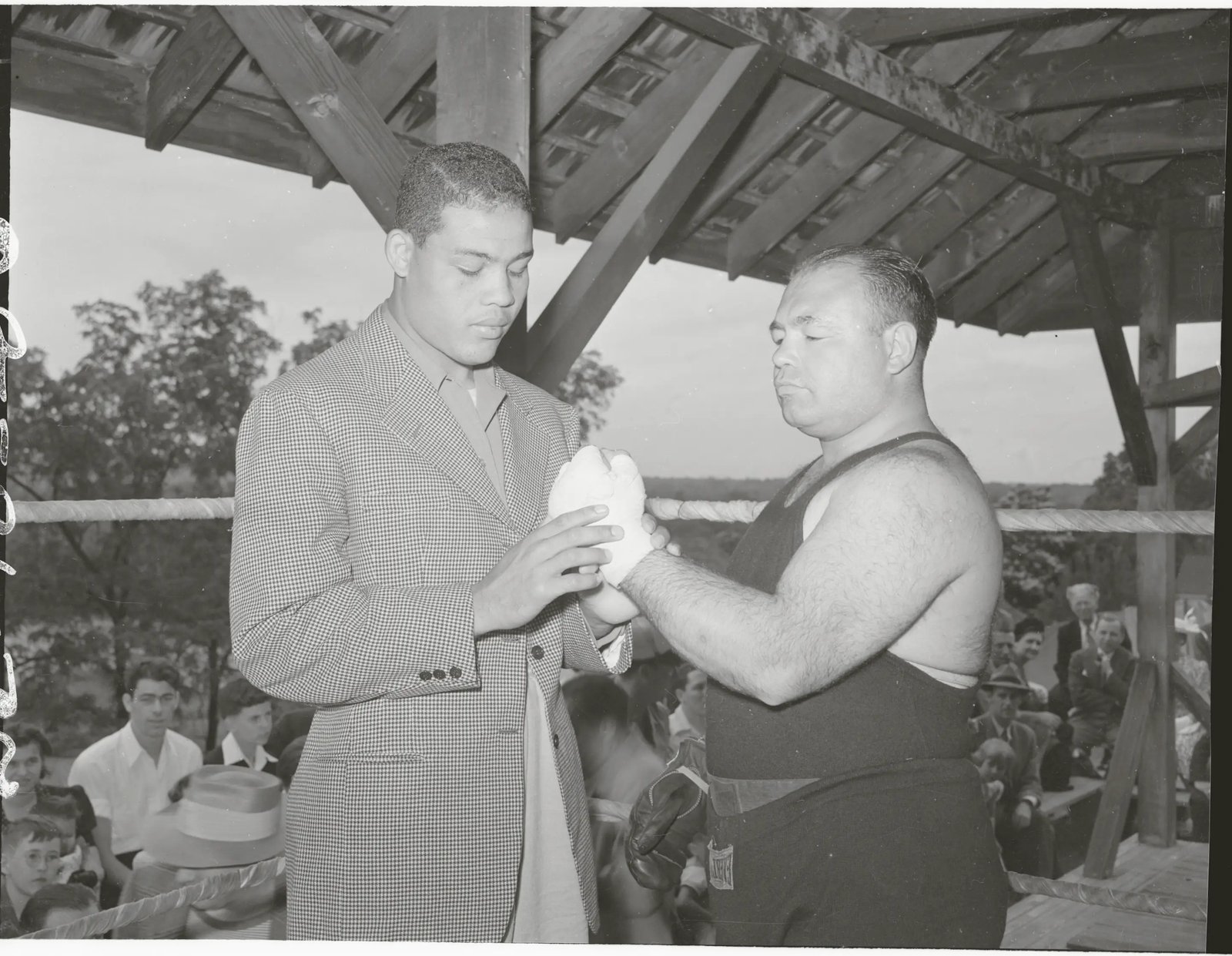

1939: Joe Louis, heavyweight champion, looms like a skyscraper over his rotund challenger, Tony Galento.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

Before the bout could be made, Galento was required to undergo a more extensive pre-fight physical, which may have been a way for promoters and the state boxing commission to cover themselves in the event that Galento was seriously hurt or even killed. Galento turned the ordeal into a comedy routine, emerging from a private exam with doctors who prodded his prodigious belly to tell the assembled reporters: “It’s a boy!”

Advertisement

Jacobs kept up the quest for headlines leading up to the bout, at one point contacting William Moulton Marston, the inventor of an early version of a polygraph, to administer a test that would determine whether or not Galento was lying when he claimed to have no fear of Louis.

The initial odds had Galento as a 6-to-1 underdog, but those odds narrowed as fight time approached. Writing in The New York Times, John Kieran sought to explain how this shift might have happened in the minds of fans and the betting public:

“In short, what they viewed as an uproarious farce at long range they viewed as a serious fight as the hour of combat drew near. Now, even the most timid person must know that his chances of being struck by lightning are slim. He can be shown the figures on the total population of this country, and the number of persons struck by lightning in the course of the year. It would be ridiculous to think that he was running much risk according to those figures. He snaps his fingers boldly at the sky. Then it clouds up. The air is sultry. Thunder is heard in the distance. A lightning storm is coming over. The wind rises with an ominous swish. The rain comes down in buckets. And the timid gent is out in the storm! Ah! Now he views his chance of being struck by lightning in a very different light. Crack! Boom! Never mind the figures now. All he knows is he might be hit. That’s the thing that grips his mind at the moment.”

There were also, especially among the press, genuine concerns that Galento might be headed for a life-altering or even life-ending beating at the hands of the peerless Louis. Kieran himself hoped for a merciful referee, insisting that, unless Galento could land a lucky punch early on, “what the live Louis will do to the lumbering Galento will be just too ghastly.”

Galento himself only increased the chances that Louis would try to hurt him grievously. Ahead of the bout, he got the phone number for Louis’ training camp in New Jersey, reportedly calling the champion often late at night, abusing him with racial taunts and even making sexual remarks about Louis’ wife. This enraged Louis, who supposedly told his corner that he planned to carry Galento in the later rounds so he might pile on the punishment.

Advertisement

Still, Herman “Mugsy” Taylor, promoter of the first Dempsey-Tunney bout, told Bob Considine of the Washington Herald that, against all common sense, Galento believed in himself.

“The fellow honestly thinks he’s going to win,” Taylor said. “Hell, he knows he can’t hit Louis, or move around with him, or box with him. He’s told me more than once that, mechanically, Louis is the greatest thing he ever saw. But he’ll admit all that and still look me in the eye and say he’s going to beat him.”

Heavyweight champion Joe Louis takes a look at Tony Galento’s right hand at Galento’s Summit, N.J., training camp.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

Some 35,000 spectators showed up to Yankee Stadium in late June to see Galento try to make good on his promises. Despite being the champion, Louis entered first. Galento entered second and made a show of walking over to Louis’ corner to display his wrapped fists for inspection. (Jacobs had accused the Louis camp of doctoring the champ’s fists in the Schmeling fight, claiming a doctor had told him that no mere human hands could do damage like what Louis had done to the German.)

Advertisement

An estimated 40 million people listened to the radio broadcast of the fight on NBC. The audience at ringside included FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, the governors of four states, one Supreme Court justice, the nation’s Postmaster General, and comedic radio star Jack Benny, among others. Back in Orange, at Tony’s tavern, more than 700 people crowded inside to cheer for their hometown hero.

As the fight began, Galento’s strategy became clear. As the much shorter, slower man, he planned to fight out of an extremely low crouch. His head seemed to hover just inches above the canvas, daring Louis to reach all the way down for him and expose himself in the process. Louis did, which created the opening Galento needed to land a short left hook that rocked Louis in the corner late in Round 1.

Suddenly, it didn’t seem like such a guaranteed execution after all. Maybe this short, fat, bald bartender had a chance, as impossible as it seemed.

But Louis was the champ for a reason. Galento might have had a puncher’s chance, but he wasn’t the only one in this fight with heart. As Dempsey (who did not attend the fight and called those who did “suckers”) had predicted, even if Louis got knocked down, “Joe is game; he can get up off the floor.”

Advertisement

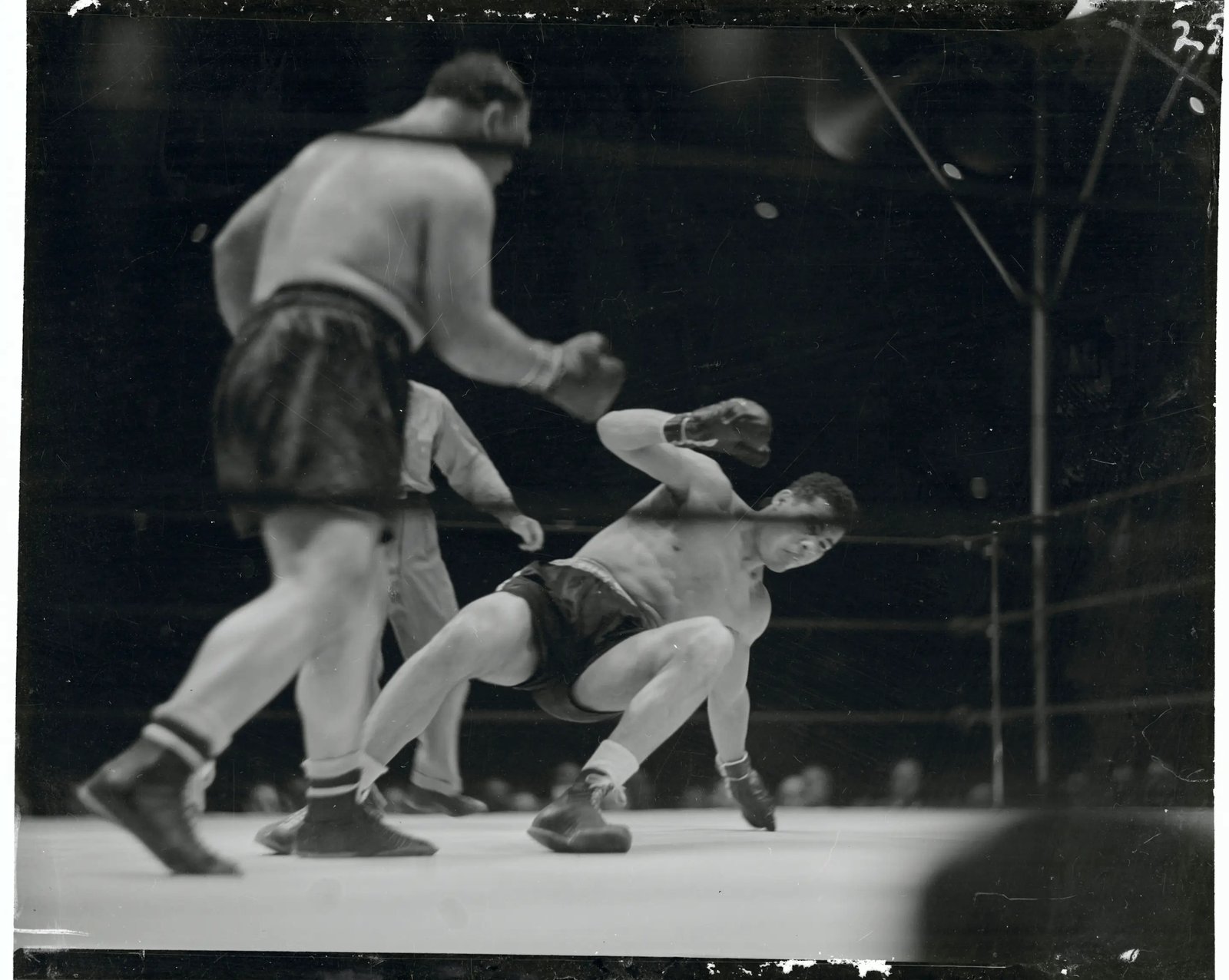

In the third, after bloodying Galento’s face and nearly closing both his eyes while dropping him in the second round, Louis was forced to do just that. A short hook from Galento caught the champ on the way in and lifted him like an umbrella in a strong wind. Louis spun around and landed on his left shoulder. For just that one instant, it seemed that Galento, the man built like the kegs of beer he loaded into his tavern each day, might go home with the heavyweight title straining across his broad waistline.

Then, as if spring-loaded, Louis popped right back to his feet. The champ was eager for payback.

Tony Galento (left) stuns the world by flooring Joe Louis with a hard left during the third round of their championship bout.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

That’s when the bloodbath really materialized. Louis was too fast, too sharp. Galento’s crouch gave way to a weary, straight-up stumble. He was too tough to go down and stay there, but Louis didn’t mind peppering his bloodied, misshapen face with as many punches as it took to make his point. Finally, in the fourth, referee Arthur Donovan caught Galento in his arms just as the challenger staggered into the ropes. Donovan is said to have looked over at Galento’s corner and told them simply: “Come get him.”

Advertisement

Louis, in keeping with his managers’ rules, kept his celebrations minimal. Galento afterward lamented to reporters that he’d let himself be talked out of fighting his kind of fight, by which he meant dirty and rough, bending the rules of boxing past their breaking point. He would go on to overcorrect for that error in his next fight, a TKO win over Lou Nova that was regarded by many who saw it as one of the dirtiest boxing matches of all time, a horrifying spectacle of cruelty from both men that appalled even seasoned observers.

Some newspaper reports praised Galento’s toughness after the Louis bout, giving him perhaps too much credit while taking Louis’ eventual triumph for granted. Lardner wrote that Galento, “whose heart is nearly as big as his vast, round, fur-bearing chest, created the best heavyweight championship fight since the Dempsey-Firpo thing when he stood up to Joe Louis and thew wild left hooks until his time, strength, and consciousness ran out in the fourth round.”

In a post-fight piece for The Ring, writer and cartoonist Ted Carroll wrote: “All the world loves a winner, but it has been shown time and again that a gallant loser is acclaimed by all. Many a winner’s fame is but momentary, while the name of a gallant loser never will be forgotten.”

Bruce Bliven, a writer for The New York Post and The New Yorker, offered a different take: “The promoter, the boxing commission, the manager, the press, just made this one up. They made up a fighter, they made up a fight, and a few more than 35,000 paid to see their brainchild. Everybody knew it was phony but the guy himself, the ‘Two Ton’ Tony Galento. Out of the words and pictures emerged their fantastic imaginary fighter. ‘Two Ton’ Tony Galento of Orange, New Jersey, fat and bald, who trained on beer and cigars and late hours behind the bar of his saloon, and said Joe Louis was a bum. … Then they put him in a ring in the Yankee Stadium against the champion, just for the fun of it and the curiosity money it would draw, forgetting of course that their made-up fighter was a man with a heart.”

Joe Louis batters Tony Galento during their heavyweight championship fight.

(Keystone-France via Getty Images)

But just a couple hours after Galento’s loss to Louis, Jacobs was already angling for a rematch.

Advertisement

“I know we gave out reports that Tony was training hard, but it’s over now and we can tell the truth,” Jacobs said. “That Galento is a marvel. He didn’t train. He was drinking, smoking big cigars, and going to bed at one and two o’clock in the morning. I know we said he was in bed early at night, but he used to sneak out at night and do everything he ever did before. If Galento almost beat Louis when he was in that condition, imagine what he would do if I really got him to train. Galento licked himself. Louis didn’t beat him. If I can get another Louis match for September, I promise you that Galento will be the next champion.”

Galento never got that rematch. He took two bad beatings at the hands of the Baers — first the former champ Max, then Buddy — had a couple comeback attempts, and then called it a career. He was enough of a name and an attraction that he could do other things for money. He had a brief acting career that included a small role as a thug in the Marlon Brando film “On The Waterfront.” He had a series of publicity stunt “fights” against animals ranging from bears to kangaroos. In Seattle, spectators watched him climb into a giant aquarium tank to wrestle an octopus, only to find that they could see almost nothing through the cloud of ink that the wily animal deployed against Galento. Later reports would differ on which animal in the tank that day did more biting.

Eventually he lost both legs to diabetes, then died of a heart attack in 1979.

Louis’ later years were not so rosy, either. He spent lavishly and was particularly generous toward family members. He pumped money into business ventures, many of them losing bets. A substantial tax debt forced him into attempted comebacks and side gigs, including some professional wrestling appearances — a line of work that Galento had also dabbled in after his boxing prime. Louis eventually made ends meet as a greeter at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, where this is a statue of him to this day.

Advertisement

But the great champ also suffered from severe paranoia at times. According to Monninger, he believed the government and the mafia were both out to get him. He frequently changed his travel plans at the last minute to confuse anyone who might be trailing him. When checking into hotels, he would slather the ceiling in mayonnaise as a protection against poisonous gases. He later admitted to cocaine use, and in 1970 was hospitalized for three months in a Colorado psychiatric hospital, having been taken there against his will at the request of his wife.

A sculpture of Joe Louis hangs during a wreath-laying ceremony at his grave on the 25th anniversary of his death at Arlington National Cemetery in April 12, 2006.

(Chip Somodevilla via Getty Images)

He forgave Galento for those late-night taunting calls, he said later. He insisted that Galento meant no harm and was simply “full of wind.” Louis also became friends with his old rival Schmeling, who often expressed regret that he’d let the Nazis use him as they did.

He’d done their bidding in the media, telling American reporters that the situation in Germany was not as dire as people believed, even denying reports that Jewish people were being persecuted back home. A few months after the loss to Louis, amid the chaotic violence of Kristallnacht, he reportedly hid the teenage sons of a Jewish friend in his hotel room, then smuggled them out of the country.

Schmeling had considered defecting to the United States as World War II ramped up, but said he couldn’t turn his back on his country. He later said he was almost glad to have been beaten by Louis in their second fight.

“Just imagine if I would have come back to Germany with a victory,” Schmeling said. “I had nothing to do with the Nazis, but they would have given me a medal. After the war I might have been considered a war criminal.”

Schmeling returned to America in 1954, in order to referee a fight in Milwaukee. First, though, he flew to New York, saying he had business there. That business turned out to be a visit to the grave of his old friend and manager, Joe Jacobs, who’d died while sitting in a chair in a doctor’s office one day in 1940. Schmeling never got a chance to say goodbye, but he disagreed with others’ assessments that it was Jacobs’ drinking and cigar-smoking that killed him in his early forties.

“How often had he made us laugh with his constant state of excitement — gesticulating, voice cracking, never finishing a sentence, working on his cigar, gasping for breath,” Schmeling said. “That’s what Joe Jacobs died of.”

When Louis died of cardiac arrest in 1981, Schmeling helped pay for his funeral. He also served as one of Louis’ pallbearers, lowering his former enemy, gently now, into his final resting place.

Author’s note: A great debt is owed to the following texts, all of which are highly recommended for readers who wish to know more about this chapter of boxing history:

“Two Ton: One Fight, One Night” by Joseph Monninger

“Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink” by David Margolick

“At The Fights: American Writers on Boxing” edited by George Kimball and John Schulian

“The Heavyweight Champions” by John Durant

Read the full article here